A Conversation with James Sale

Interview by Carol Smallwood

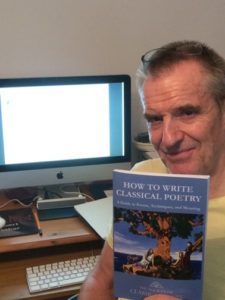

As well as being a management leader and the creator of Motivational Maps, which operates in 14 countries, James Sale has published eight collections of poetry and also books on teaching the writing of poetry. His poems have appeared in many UK magazines, as well as the United States: he was the winner of The Society of Classical Poets Poetry prize for 2017, and winner of their Prose prize for 2018.

James has been a writer for over 50 years and has had over 40 books published. Specifically, on the teaching of poetry, his titles include The Poetry Showvolumes 1, 2, 3 (Macmillan/Nelson), Macbeth, Six Women Poets(Pearson/York Notes), as well as titles from major publishers such as Hodder & Stoughton, Longmans, Folens, and Stanley Thornes.

Carol Smallwood (CS): When did you begin writing poetry and who are a few of your favorite poets?

James Sale (JS): As for many others, at puberty – 14 – when the Muse visited me for the first time, and for the first time I heard a poem being read aloud and was astonished by it. I immediately thought: “I must do that” and I did. I was in Mr. N. A. Thomas’s English lesson at the time. Aside from the greats, who are in another class – Homer, Dante, Shakespeare, and Milton – the lyric poets I especially love are Herbert, Rochester, Coleridge, Keats, GM Hopkins, and Yeats. Of contemporaries (since poetry did not stop with the birth of my mother, and although I completely disagree with his underlying, atheistical philosophy), Tony Harrison is a force to be reckoned with; and I am on record at The Society of Classical Poets’ website for claiming that your own Professor Joseph Salemi is a major poet, though his Muse – one of savage satire – is not my preferred style now. That said, when I was younger, Rochester, a vicious satirist, pleased me greatly. I delude myself into thinking I am more kindly now.

CS: Do you think being involved in management motivation relates to your literary writing?

JS: That is an interesting question, and the answer has to be yes, because everything is connected. When one looks back on the arc of one’s life – and truly begins to understand it – all is incredible, and all is a miracle; indeed, a miracle of ‘rare device.’ You may remember the actor David Carradine who starred in the Kung Fu series. He memorably said: “If you cannot be a poet, be the poem.” The poet makes a poem, and we make our lives. If we have not made our lives, then we are already dead; but the strange thing is – there is another force influencing our lives in exactly the same way that the Muse starts to write our poetry. And like the Muse, there is an unpredictability about it – about God basically. Those with no Muse in their lives or poetry must suffer their fate; those whom the Muse/the God speaks to, encounter their destiny. How it affects my writing would, alas, take an essay to explain, so I’ll move on for now!

CS: What is your most recent poetry collection, Inside the Whale, about?

JS: Actually, Inside the Whale is my penultimate collection. The Lyre Speaks True is my most recent book. But there are no accidents and as you have nominated Inside the Whale, then let me talk about it. This collection is a metaphor for being in hospital – as Jonah was swallowed whole by the whale for three days and nights, so I in 2011 suddenly collapsed and found myself in the hospital for three months. Unbeknown to me, I had a malignant cancer, one of them the size of a grapefruit inside me. After two major operations, and one near-death experience, I finally emerged from hospital into the light, into the land of the living, an ‘older, wiser man’, and one, like Jonah, transformed by the extremity of my experience – and the saving grace of God that brought me back when I was nearly dead. The poems detail some of my experiences in this inferno. Perhaps, if I may be permitted to quote from one short one, your readers will get a flavor:

I Heard the Lord

I heard the angel, I heard the Lord –

Dying, and his word came to me.

Lying there, in that dumb sweat, no word

Expressing what it was not to be.

Confessing only in my tear, torn eye:

What was the soul able and full of?

Not – whatever men think, contrariwise,

This earth of nothing, this lack of love

With condemnation’s fearful, fevered pitch!

No, I say, I heard the Lord.

Go, he said, rise up and touch –

And as I did – life struck its chord.

CS: One of your books (I was pleased to note) is Six Women Poets: please share who they are and how you selected them?

JS: Yes, the Six Women Poets are all popular British poets who are on UK examination board syllabuses; in other words, they are studied in UK schools by 15-16-year-olds for exam purposes. I was asked, therefore, specifically to write review notes on these poets and their poems to help students pass their examinations; so, I did not get to choose them! The six are: Gillian Clarke (currently the Poet Laureate of Wales), Grace Nichols (a Caribbean poet who emigrated to the UK in 1977), Fleur Adcock (actually born in New Zealand, but perhaps the most classical of them all), Carol Rumens (greatly influenced by Plath and Sexton, and the American women poets generally), Selima Hill (a poet focusing on personal experience and its meanings), and Liz Lochhead (who was the National Poet of Scotland). A diverse group, representing a lot of diversity in the UK. One final comment, though, would be to say to all poets, male and female, if you want more sales of your poetry collections, then make sure you get on an exam syllabus somewhere!

CS: What is the Royal Society of Arts and how did you get elected a Fellow?

JS: I was a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts (FRSA) for ten years, but resigned my fellowship a couple of years ago for reasons I will come to. But the full title of the RSA is The Royal Society of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce, which gives a slightly different nuance to its focus. It was founded in 1754 – before even the American Republic existed – and it was a child of the Enlightenment. What Enlightenment really means, of course, is secularism, humanism, atheism. It’s quite masked; many religious types belong to the RSA and see no problem, but I increasingly found myself irked by the heresy the ‘enlightenment’ always presumes: namely, the Pelagian heresy. In short, the RSA subscribes to the view that society and human beings are perfectible – they are busy creating a brave new world, and in my view now this is all utopianism, which will fail. Putting this in a ‘classical’ framework: we need to improve the world and use all our strength to do so, but to think we can do this without or in defiance of the gods is what the Greeks called hubris. And there is so much of that about. But thank you for reminding me: there are still places up with my name framed with FRSA, which I need to take down. How did I get in, in the first place? My good business friend, Tim Bullock, an investment ace, was a Fellow and proposed me: so, you see, there is an example of the business and the art world mixing.

Currently, I am a member of another London club (but with overseas links to other worldwide and in places such as New York, which I am visiting next year): The Royal Over-Seas League. That suits me better.

CS: What is The Society of Classical Poets and what prizes did you receive from them? Can anyone submit poetry?

JS: I love The Society of Classical Poets and everything about the organization and its inspirational leader, Evan Mantyk – with the possible exception of the rancor of some of its members! It exists to promote real poetry: that is to say, poetry with form, for without form there can be no poetry. Poetry is form. It is true, in case any doctrinaire free-versers are reading this, that occasionally, a true poem exists that seemingly is ‘free,’ but this is an extreme exception; and it is a not a starting point. The idea that someone who can’t write a coherent sentence is somehow a poet because they splash words on a page is part of a profound and immoral political agenda. People easily forget that the greatest modernist – and free-verser – of the C20th, TS Eliot, didn’t really write ‘free’ verse: a cursory study of the Wasteland reveals iambics everywhere, and rhyme as a matter of course. It seems to be the view that has taken hold that writing in conventional forms means one is ‘conventional’ – as if that were a bad thing. The overemphasis on the individual at the expense of society is one reason why the West is rotting internally. The Society of Classical Poets is seeking to reverse this in its domain of poetry. So anyone can submit a poem, but it is pointless submitting ‘free verse’ and post-modernist claptrap. Alongside the insistence on form is the requirement of beauty – poems should be beautiful even when dealing with ugly subject matter. Take Wilfred Owen: his poems on Word War 1 create a terrible and terrifying beauty. There is nothing sentimental or sloppy there about using form.

As for prizes, I am proud to say I won Second Prize in their 2015 Poetry; First Prize in their 2017 Poetry competition; and I have also won First Prize in their 2018 Prose Competition for my 4-part series of Muse articles, which I recommend to anyone wanting to know more about poetry and its true origins. Past winners are not considered a second time, so I encourage all your readers to enter this year’s competition – it’s free to enter.

CS: Please tell readers about the Cantos you are writing. What is terza rima and why did you choose it? I found the form very challenging to write and cannot imagine a sequence:

JS: Thank you for this question. Ultimately, true poets want to be challenged by the biggest mountain they think they can climb. Of the 9 Muses, Calliope is the Muse of epic poetry, and since I encountered Milton in my early 20s and his Paradise Lost blew my mind, I have wanted to write an epic. However, as I have experimented with blank verse, I have found it impossible to attain the gravity that epic demands. As Keats found, with his two Hyperion fragments (awesome as they both are), one ends up sounding like sub-Milton. Recently, I started re-reading Dante’s Divine Comedy; also I went to Ravenna to visit his grave. And it all clicked: the terza rima form was underused in the English language (Shelley being the best exponent of it in his unfinished The Triumph of Life), it was ideal for narrative, and I had been to hell in hospital, had had a near-death experience and been taken out of the body to another place and experienced the divine, and what with some other matters as well, I reached the conviction that I could write a psychological divine comedy in English – the English Cantos – modeled on Dante, in which I visit hell, purgatory, and heaven, but perhaps in a more restrained 33 Cantos.

I have written nearly six of these now, and the first three have appeared on the Society of Classical Poets website. I’d appreciate any of your readers visiting, reading and commenting on my work:

http://classicalpoets.org/canto-1-by-james-sale/

http://classicalpoets.org/canto-2-by-james-sale/

http://classicalpoets.org/canto-3-by-james-sale/

There is also a dramatic YouTube reading by my youngest son, Joseph Sale, (a fabulous novelist actually — published by a New York press: see The Darkest Touch) of part of Canto 1.

It is extremely difficult to write in terza rima partly because the English language is poor in rhymes compared with Italian. Dorothy L Sayers did a masterful translation in the 1950s, and Peter Dale did a good one in the 1990s, but many translations stick to prose or blank verse, or variant rhyming: I love the new translation by Clive James, which is not terza rima but does use rhyme. He has some wonderful and idiomatic turns of phrase. For example, one of the counterfeiters in hell (keep in mind that counterfeiters produce the ‘not’ real thing) says: ‘In Hell everything is real.’ Wow! How well my use of the form stands up only your readers can judge, but for myself so far I am pleased with what I have done, and I think the whole thing makes for a gripping read. The thing is: terza rima is ideal for narrative: the interlocking rhymes propel the story sense forward. Whereas, for example, Spenserian stanzas do not.

About the Author

James Sale is the Creative Director of Motivational Maps Ltd, a training company which he co-founded in 2006, and the creator of the Motivational Maps online diagnostic tool used by over 400 consultants across 14 countries. He has a poetry website at http://jamessalepoetry.webs.com and a personal website at www.jamessale.co.uk

About the Interviewer

Carol Smallwood is a multi-Pushcart nominee; she’s founded and supports humane societies, serves as a judge and reader for magazines; her recent poetry collection is In the Measuring (Shanti Arts, 2018).