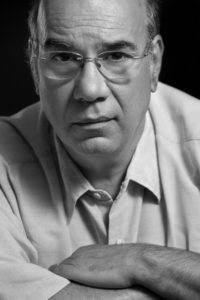

A Conversation with Jay Parini

Lowestoft Chronicle interview by Nicholas Litchfield (March 2014)

An avid writer for more than forty years—his first book, a volume of poetry, was published while he was still an undergraduate student—Jay Parini has authored dozens of books, from bestselling novels like The Last Station, which was turned into an Academy Award-nominated film, to widely praised poetry collections like Anthracite Country, described as “superb” in The Sunday Times and “a remarkable book” in the Library Journal. He has also written critically-acclaimed biographies of John Steinbeck, Robert Frost, William Faulkner, and Jesus, and edited many volumes of anthologies and literary criticism. His biography, Robert Frost: A Life, won the Chicago Tribune Heartland Prize for best non-fiction book of the year.

In a recent interview with Lowestoft Chronicle, Jay Parini discussed his poetry, his latest biography, and those early days of his writing career studying overseas in Scotland.

Lowestoft Chronicle (LC): I remember you saying that you started off as a poet, your first love was poetry, and you consider yourself primarily a poet. You published your first book, Singing in Time, in 1972, while you were an undergraduate student at the University of St. Andrews. What made you decide to study in Scotland in the first place, and what made you want to remain there? Was Starglow Press (the publisher of that first book of poetry) a small independent press or was it university run?

Jay Parini (JP): I went to Scotland for various reasons. Mainly, it was to get away from the US during the Vietnam War era. I felt threatened by my draft board, and I felt disenchanted with this country. I also had a kind of fantasy about Britain – had read so much literature set there, that I wanted to see for myself. I needed to get away is the short summary. And I did. Seven years there. I loved it, mostly. Nobody loves everything all the time, but Scotland was pretty much a good experience and often a great one. Met such interesting people, and learned so much. The little press that published my first poems was an independent and short-lived press in Fife. I knew the guy who ran it, a local bookseller. He did a few books then folded. But I very much thought of myself as ONLY a poet.

LC: You always begin each morning by writing poetry. You turn to fiction and criticism only after you’ve finished with your poetry for the day. Anthracite Country, your next book of poetry, wasn’t published until 1982. Was the reason for this because you wanted to focus on other forms of literature or because of publishing commitments with Little, Brown & Company and Scribner, etc.?

JP: Poems take a long time for me. Unlike prose, which I write easily and swiftly. I don’t like to rush a poem. I like them to sit for a long time. I figure that if, in a lifetime, I write a dozen good poems, that is enough. So that’s my goal. I really only bring out a volume once every decade or so. More or less. Of course, the prose projects get in the way; all of the criticism, novels, biography, and other things take up writing time. I don’t think I could, in fact, just focus on poems. I need the room in my head for lots of projects. I like that feeling of abundance.

LC: While teaching at Dartmouth College, you started getting poems published in The New Yorker and The Atlantic. You also co-founded the quarterly literary magazine, New England Review. When did you start sending out your work, Jay? What was the first piece you had published? And what made you decide to start a literary journal? Do you have much interaction with the magazine anymore?

JP: My first poem appeared in Scottish International, no longer in existence. I remember that day with great joy. I don’t even remember what poem they published, however. Probably one I no longer even own. I had poems in The New Yorker, The Atlantic, and Poetry in the same year. Maybe 1978. Something like that. I sent poems to all the quarterlies, etc., and published in most of them: Hudson, Sewanee, VQR, Paris Review, and Yale Review. I don’t pursue publication anymore; not in that way. Once in a while, I feel moved to send a poem somewhere, but usually not. I have only a very peripheral involvement with New England Review, which, of course, I co-founded. The editors are good friends now.

LC: I’ve heard you tell a great story about James Atlas approaching you to contribute to the ICONS biography series and, when you proposed to write one about Jesus, he almost fell off his seat. Prior to writing the biography, I know you originally intended to write a novel about Christ. Having done so much research into his life, will you be putting your notes toward a novel at a later date?

JP: That’s a true story. Jim Atlas almost fainted when I suggested Jesus as a topic. He had suggested Sofya Tolstoy. I preferred Jesus. It’s been a success, I think. Lots of enthusiastic readers. I get countless emails and letters about it. My plan is to write two more books in the coming few years with some religious angle. I want to write a book on how to be a Christian, and I want to write a novel about Saint Paul.

LC: I read that you’re in the process of writing a biography of Gore Vidal, to be published by Doubleday in 2015. As executor of his literary estate and a longtime friend for thirty years, as well as being an acclaimed biographer, you’re the perfect person to write the book. But it does sound like an immense project, especially with Vidal’s work branching into so many different areas. “The good biographer must find a mythos, or story, that will help to tame the myriad facts of the subject’s life,” you once wrote. Is there a particular aspect of his life and work, a story thread that you intend to focus on?

JP: I’m halfway through the Vidal book, which I’ve been (in a sense) writing for twenty-five years. I’ve got endless material. Endless. Some good stuff, mostly in the form of interviews with Gore and Howard (his partner) and various friends who knew Gore well over many years. I know this life well. It’s a question of tone. That is evolving as I write. I may have to rewrite a lot of stuff. Some bits and pieces of this book were written in the early nineties, when I was planning to write a bio of Gore, but pulled back because I knew he’d be impossible about it.

LC: Over the years you’ve written many wonderful essays for The Chronicle of Higher Education. Some of the most fascinating ones were on authors like G.K. Chesterton, Henry James, and Rudyard Kipling. Your essay “Ruddy Good Show,” where you write about attending a service of remembrance for Kipling, is a particularly good one. Kipling, you said, was one of your favorite writers and an underrated poet, and you’ve even visited his 17th-century manor house in east Sussex and his house in Brattleboro, Vermont, where he wrote The Jungle Books. Have you considered writing a full-length biography of him or any of these authors? Or will Vidal be your final biography for the time being?

JP: I won’t ever write another conventional biography. I will, though, write more biographical fiction.

LC: You’ve met and worked with some immensely significant writers, actors, and artists. Some you’ve told wonderful anecdotes about and some you’ve only mentioned in passing. One of those I’d love to learn more about is Graham Greene. You knew Greene personally, visiting him in Capri and, later, in Antibes toward the end of his life. You even wrote him into The Apprentice Lover, your sixth novel. What was Greene like as a person? I read an article by you where you talk about the books on his shelf, and it made me wonder if you talked about each other’s writing. What did you learn about Greene from your conversations with him?

JP: I liked Greene very much. He was warm and seemed interested in what I was writing. I gave him one or two of my books. I didn’t know him well, so it’s hard to go into much detail. But there is a certain interest in meeting and talking with writers you admire. I liked meeting Borges, Neruda, Anthony Burgess, Auden, Anthony Powell, etc. Just to get a whiff of their presence.

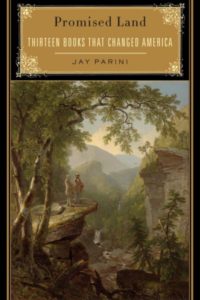

LC: You’ve traveled widely over the last four decades and lived and worked in numerous countries. Wherever you’ve been, you seem to have always made the most of your time in a location. Even as a student in Scotland, you ended up meeting W.H. Auden on an excursion to Oxford. On an unintended night out in north London, you watched a lecture by Lord Melvyn Bragg that inspired you to write Promised Land: Thirteen Books That Changed America. While living in Italy, you ended up having dinner with Gore Vidal, who lived nearby—a stranger to you at the time. Do you have any regrets, Jay? Any occasions you’ve thought back on as missed opportunities? Perhaps a project or event you passed up on that you later wished you hadn’t or a writer you could have met with but didn’t?

JP: Well, I tried to make the most of being in a place. I was alert, looked around, wondered who might interest me. Do I have any regrets? I have endless regrets. They are mostly personal failings. Failures to be sympathetic enough or help someone. I dislike a lot of my own books, and wish I had done a better job on them. But I like a few as well. I suppose that life is like this. Generally, I feel as if that, given my limited talents – and I’m not being modest – I’ve managed well enough as a writer. I’m hoping to have a stretch of time ahead of me when I can write my best work. That’s the plan!

About the Author

Jay Parini, a poet, novelist, and biographer, teaches at Middlebury College. His books of poetry include Anthracite Country, Town Life, House of Days, and The Art of Subtraction: New and Selected Poems. His novels include Benjamin’s Crossing, The Passages of H.M., and The Last Station. He has written biographies of John Steinbeck, Robert Frost, William Faulkner, and Jesus. Among his various works of nonfiction are Why Poetry Matters and Promised Land: Thirteen Books that Changed America.

About the Interviewer

Nicholas Litchfield is the founding editor of Lowestoft Chronicle. You can read more about him at his website: nicholaslitchfield.com