A Conversation with Michael C. Keith

Lowestoft Chronicle interview by Nicholas Litchfield (January, 2013)

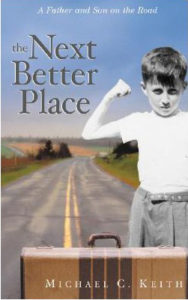

His memoir, The Next Better Place, described by Publishers Weekly as “a hitchhiker travelogue that reads like Little League Kerouac,” has been likened to Angela’s Ashes and praised by the likes of Larry King and Augusten Burroughs. His short stories have received praise from iconic science fiction writer Ray Bradbury and The Huffington Post. Surprisingly, Michael C. Keith is actually better known for his scholarly books on broadcast media, radio in particular. He has authored some two dozen books on electronic media, one of which, The Radio Station, is the most widely adopted textbook on radio in America, and Waves of Rancor: Tuning in the Radical Right, which he coauthored with Robert L. Hilliard, was on President Clinton’s summer reading list.

Recently, Lowestoft Chronicle caught up with Michael C. Keith to discuss his poignant and comic memoir, his fiction and academic works, and his literary tastes and influences.

Lowestoft Chronicle (LC): The Next Better Place is a brazen account of your travels across America with your father, Curt, in 1959 (from Pittsburgh to Indianapolis, Denver to Los Angeles, Las Vegas to Fort Worth, and back to Albany). How would you describe the process of writing the book, and what made you decide to tell the story from the perspective of an eleven-year-old?

Michael C. Keith (MCK): The process was an ongoing and lengthy one. I had it in mind to write about my unique childhood from the time I became an adult, but it took decades before it was ripe for the telling and then only after outline after outline. The writing went through several stages. The memoir first manifested in the form of an ill-conceived screenplay (one is currently being written by a professional screenwriter), then it became a full-length manuscript with prologue and epilogue, and finally it morphed into a penultimate version, sans prologue and epilogue. I had sent it out to tons of publishers and agents, and you know how that story goes. Finally, I sent it to the agent of a friend, and they liked it. After a dozen rejections, it was picked up by Algonquin Books. That was an exciting day, to say the least. You really get to the point that you think it will never be sold. Having it contracted by a prestige house like Algonquin was the frosting on the cake, and my editor there turned out to be fantastic. She really related to the story because she had a young son. So once it found a home, things went very smoothly. Searching for and finding that home was almost a greater challenge than writing the book.

Actually, the writing went well once I recognized what needed to be done to the manuscript to make it salable. I had this overwrought vision about telling the story of my entire life by employing a lengthy (windy) prologue and epilogue. That was a mistake. The core of the manuscript was the book. The prologue and epilogue just got in the way of the essential story. It took quite a while for me to realize that. I well remember the day I realized what had to be done. It was an epiphany of sorts. I was walking across the Boston College campus on my way to teach, and it suddenly occurred to me that I had to dump the front and back matter in the manuscript. At that same moment, the title came to me, too—The Dream of Motion. I loved that title, but my editor thought it sounded like the title of a book about running. She suggested a phrase from the book—The Next Better Place—and it became the title. I still prefer The Dream of Motion, but I suspect I made a wise concession.

As far as deciding from what perspective to tell the story, that was a non-issue. From the start, I knew it should be told by my eleven-year-old self. It seemed recounting the experience from a child’s point of view would allow me to get the most out of the narrative. The child is just old enough to see the world as both a scary and wondrous place. That combination gives you a lot to work with. Initially, I feared it would be very difficult to capture the mindset of an eleven-year-old, but it turned out to be a very natural and easy writing experience. Maybe having a stunted maturity helps—I jest (hopefully).

LC: When not on a Greyhound bus, daily life revolves around flophouses and homeless missions, beleaguered by perverts and lowlifes, or getting into trouble (at one point, you’re charged as an accomplice to an armed robbery). Considering the hardships you faced on your travels—the constant hunger, your routine disappointment in your father, your grim surroundings, and the cast of sleazy characters you meet—did you find it difficult to write about your experiences in The Next Better Place?

MCK: Not as you might think. Having lived with the experience for so long, I gained some distance and was able to view it with a certain objectivity. It all seemed like a quirky road movie to me as I got older. Fortunately, my father was a pretty benign guy, who, in his strange way, tried to look after me. Despite some gloomy periods involving his drinking and my hunger, it seemed like a high adventure to me. I had the kind of freedom few kids have, and that appealed to me. No school, no bedtimes, no baths more than compensated for the rough spots. Many times during the writing process, I laughed out loud recalling the ridiculousness of some of our situations. Maybe humor is a good way to cope with the bizarre. The reaction of readers is interesting. Generally speaking, women seem to view my situation as a kid with sadness and sympathy, while men often see it as plain funny and strange. It was certainly all of those things and a good deal more.

LC: In terms of closure, the book ends with the reader speculating about many things—did you continue on to Florida with Curt, or did the journey end in Albany? After your return home, what became of Curt, and how would you describe your relationship with him? What impact did these travels have on the rest of your life?

MCK: Actually, the paperback version, that published a year after the hardcover, has an outcomes chapter. We did head out to Florida, and for the next several years, continued our gypsy-style life. I broke away at seventeen when I convinced my father to sign me in to the army. Best thing I ever did. Helped me put things in perspective and gave me a better understanding of what my life with my father had been about. He continued to drink, but no matter how old I was, he always remained close by. There was a definite attachment, if not dependency, on me. I often bailed him out of tight situations caused by his alcoholism. On the brighter side, he often helped babysit my daughter, who developed a close relationship with him. It was a sort of redemption for him, but I always felt a level of anger for his depriving me of a normal childhood. In the end, though, my uncommon childhood may have had a positive impact on me in the sense that it provided me with a great model of how not to conduct one’s life.

LC: Why didn’t you write a further memoir about your travel experiences, and is there any possibility that you will do in the future?

MCK: The idea of a sequel has been in the back of my mind since the publication of The Next Better Place. It is, at the moment, being adapted for the screen by an LA screenwriter with some credentials, but as I’m sure you realize, getting anything to screen is a real long shot. Unfortunately, the book only did modestly well in terms of sales (although it was a critical success), so Algonquin is not keen on a sequel. They have encouraged me to write a novel, and that I may do some day.

LC: I’m surprised to hear you say The Next Better Place wasn’t a commercial success, considering the extensive media exposure it got and the fact there’s also an audio version available.

MCK: As fate would have it, the book was released the first day of the so-called “Shock and Awe.” Turns out the start of the Iraqi War impacted book sales and kept people too preoccupied to buy books for a while. At least that’s the prevailing wisdom. The book made enough to pay back my advance, so I suspect around five thousand copies were sold. Not sure about that figure, but it seems to calculate. It was a disappointment, because we all thought it would do better. Apparently, it did well enough for Algonquin to publish it in paperback, and now it’s in ebook format (Kindle and Nook), so it lives on. And there is the possibility of a film version someday.

LC: There’s a moment in the book when you’re listening to a radio show (Don McNeill’s Breakfast Club) in a boardinghouse, and you say to one of the boarders, “I’m going to be on the radio someday, too.” Surprisingly, this is one of the few references to radio in the entire book. Did radio play a significant role in your childhood? What made you want to be a radio broadcaster, and how did you get involved in that field?

MCK: Radio was ubiquitous in the 1950s, so even in the flophouses, there often was an old radio to listen to. It became one of my primary forms of entertainment and distraction. It also served as a companion when my father wasn’t around. I would often fantasize being on the radio, so I guess it was no surprise that I would consider a career behind the microphone. As soon as I was discharged from the service, I went to radio school. After getting my certificate, I got a job at a small New Hampshire station as an announcer and, from there, worked my way into larger markets. I spent a dozen years in the medium in various jobs: production director, newsman, account executive. Eventually, I longed for something different and went to college on the G.I. Bill. Many years later, I became a college professor and am now nearing retirement after thirty-five years in the classroom teaching communication studies. During that satisfying period, I wrote several books on electronic media, mainly centered on the cultural aspects of radio.

LC: Voices in the Purple Haze: Underground Radio and the Sixties, is an interesting account of the rise and fall of commercial underground radio, which rejected established structures of Top 40 radio. Evolving around 1966, it peaked between 1967 and 1969, before fading in 1971. Studio memorandums, station mandates, and sample playlists aside, your book is largely comprised of interviews with 32 prominent figures of freeform radio in the U.S. What made you decide to write about this very brief counterculture movement? How challenging was the process of rounding up so many of these radio personalities and getting them to share with you their opinions? And were there any radio practitioners (Tom Gamache, Bob Fass, Larry Yurdin, Buck Matthews, and Bob McClay, for example) that you wish you could have interviewed, but didn’t get the chance?

MCK: I’m a youth of the 60s and a radio scholar, and so the role of the medium during that period fascinated me. I also knew that the story would be much better told by the people who lived it. As an old radio guy, I had a number of contacts, which led to other contacts, etc. Soon I had a marvelous bunch of underground radio pioneers to draw from. Of course, there’s always someone you miss, but I’m quite satisfied that the people I got very comprehensively represented this unusual and unique form of radio. Of all the monographs I did in the area of radio studies, this is one of my favorites. The frosting on the cake was that the book was very well-received by the underground radio community.

LC: The Radio Station is your most successful book and considered a seminal book on radio broadcasting? Can you explain why the book has proved to be so popular?

MCK: Up until the time The Radio Station was published in 1986, radio books were fairly bland and, often, somewhat dated in their focus. That is to say, they were short on visuals and out of touch with the realities of the contemporary radio marketplace. I conceived a text that would show as well as tell and tell from the perspective of industry people. It was a formula that worked, and The Radio Station became the most widely used text on its subject in the country. It’s also used throughout the world, and because of that, I’ve been invited to lecture in Russia, Indonesia, Spain, etc. Now it’s about to morph into Keith’s Radio Station, co-authored by two excellent media academics. I reached a point after producing eight editions of the text that I no longer cared to continue, but the publisher did. So now I have my name in the title, and that is very gratifying.

LC: Having published three short story collections recently, have you moved away from academic writing to focus on fiction, or do you have another nonfiction book in the pipeline?

MCK: Actually, four story collections. My newest, Sad Boy, was just published by Big Table Publishing, an excellent small press. I tired of writing academic books (thirty-two volumes in all) so sought refuge in fiction about six years ago, starting with a young adult novel, Life is Falling Sideways. After it, I became involved in short story writing and found I had somewhat of a facility for it. Now, here I sit with 130 stories published (with several writing award nominations) and contemplating what’s next. I’m sure more short stories are in my future, but longer form fiction is likely up the road, too. That said, part of me thinks: keep writing short stories and maybe someday you’ll get really good at it. That’s a worthy objective, but I get itchy to try other things.

LC: I’ve heard you say in an interview that TV shows like The Outer Limits, The Twilight Zone, and Science Fiction Theatre influenced you growing up. Were there any particular writers, books, or magazines that shaped your writing?

MCK: B horror and sci-fi movies were also an influence. Among authors most intriguing me at a young age, I’d say Ray Bradbury, Kurt Vonnegut, Isaac Asimov, and Stephen King (later on) had some influence on me. However, again in the interest of full disclosure, I must admit that I was never a big reader of speculative fiction or short stories. I liked novels featuring contemporary humor, irony, and angst. Always loved Philip Roth and John Irving, to name only a couple. Back in the day—when I had flowers in my hair—I was a fan of Richard Brautigan. The literary genre I like best is biography (mostly about authors), even ahead of fiction.

LC: I hear the dark novella you’re working on is an extended version of the short story “The Waiting Bell” (published in Sleet Magazine). Is this correct? What made you want to develop this story and why a novella?

MCK: You are quite correct—you have good spies. The story idea came to me when I read an article about the waiting houses in Germany during the 19th century plague. It struck me as a wonderful idea to spin into a Gothic horror story. That bodies were actually stored in warehouses until it was determined beyond a doubt that they were dead absolutely intrigued me. Stories that come about through casual encounters are a real gift from the writing gods. I’ve had many such encounters and consider myself lucky for it. “The Waiting Bell” turned out to be one of my stronger stories. People really had an emotional reaction to it. Rereading it recently, the idea for a full-length treatment came to me. Much is already outlined, so I’ll see if it really does lend itself to the novella format. I hope it does.

LC: How would you describe your latest book, Sad Boy? How does this book differ from your last three short story collections?

MCK: I think Sad Boy is a bit mellower and somewhat less speculative than my previous collections in that the stories take place more in the so-called realm of reality. Of course, some are way beyond the boundaries of reality, but many deal with males facing challenging real-life situations and issues. That said, Sad Boy is filled with some pretty twisty/twisted tales. I can’t help that because I have a pretty twisty/twisted creative imagination. Besides, who wants to write about real life? Much of it is too mundane for my pen. As a sad (old) boy myself, I’m drawn to write about those dark corners.

LC: What inspired “Gertrude’s Grave,” your latest short story for Lowestoft Chronicle? How did this macabre tale come about?

MCK: I’ve been doing a lot of reading about the Lost Generation lately, so Gertrude Stein was on my mind. I decided to look up where she was buried and discovered it was in Paris. After that, one thought led to another. That’s kind of how most of my stories manifest. Something triggers my curiosity and the race is on. I guess that’s true of many writers. Thank God for Google. Given the weirdness of many of my tales, I think of the Internet search engine as the “Wizard of Odd.” It’s a great and powerful resource.

About the Author

Michael C. Keith is the author of two dozen books on electronic media, four short story collections, a young adult novel, and an acclaimed memoir. He also co-edited a found manuscript by legendary writer/director Norman Corwin. Keith teaches Communication at Boston College.

About the Interviewer

Nicholas Litchfield is the founding editor of Lowestoft Chronicle.